Work Log Day 181

The past three months have shown very little progress until very recently. I eschewed some common CNN advice when I began this project as well as misunderstanding another. While I would have likely had a better model months ago if I had followed the best practices, I doubt I would have learnt as much.

Subtract the mean value from images!

When I began researching CNNs for this project, I commonly came upon the recommendation of subtracting the mean pixel values from each image. I decided against this due to a few factors. The biggest factor was that this is machine learning, and its suppose to be amazing. Thus I decided that if the original images were good enough for me, they should be good enough for my model. Another reason was that to subtract the mean, I had to track the mean value. This seems like an inane reason to not try something, but my bigger concern was that models were less portable, relying on a mean value to be effective. Thankfully I was able to fix this using a custom layer that stores the mean value and handles everything automagically. The last reason was that I am running BatchNormalization, so that should take care of the need to subtract the mean, right? It makes sense now why that isn’t the case, realizing that normalization shifts the distribution of the data as well as reduces by the mean.

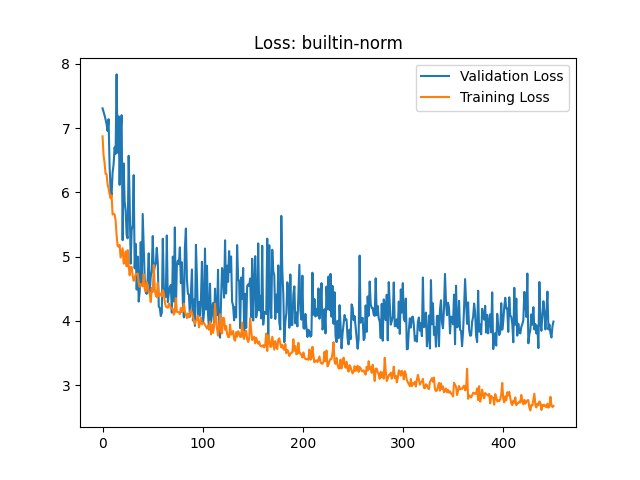

After having removed the mean, I found the validation loss to be much more stable, resulting in loss graphs much more inline with what I had seen online as ‘good’ examples. Below is such a loss graph. While it is still quite ‘jumpy’, there are fewer true outliers in the validation loss as it was before.

Data Augment on the fly

Early on I realized that I was going to have a hard time generating the number of images necessary to train a good model. Thankfully data augmentation was there to save me, and I went to town flipping all of my images. Saving all of these flips. This had the desired effect of improving my model performance, however eventually I ended up at ~30,000 images and a typical epoch taking 400 seconds. Correctly partitioning the images and their flips also became an issue, as if a flip of an image ended up in validation that was already in the training set the results were harder to interpret. Honestly I don’t think I ever got that right, and only realized the true depth of the problem after switching to data augmentation on the fly.

Upon swapping to data augmentation using the Keras preprocessing layers, I was able to train on ~7,500 images with data augmentation in about ~80 second epochs. This significantly reduced the time it took to evaluate model modifications, which allowed me to make some changes that actually made differences.

Simplify

Once the model no longer took days to train, I could make more changes. The most significant was to remove all of the spatial dropout that I had added. Interestingly enough it resulted in my model improving, with an MSE reliably around ~75. I had started to become suspicious of the spatial dropout as while Andrej Karpathy talked about them in his talks, I saw few uses in the models I could find. I wish I understood exactly they don’t seem effective, my best guess is that it is blowing away data that is crucial to learn on.

I found I could also remove the secondary BatchNormalization layer. It didn’t make much difference one way or the other, but I was always confused why I needed two in a row. It seems like it helped address the fact that I hadn’t subtracted the mean, but after I had taken care of that it was just pointless computation if the loss says anything.

The only downside in all of this is that the model has gone from being ~10MB to almost 70MB. This was mostly as I had been trying to increase the density of the network after the convolutional layers to improve performance without success. Once I had put all the other changes in place I found that the denser network was necessary to keep the added performance. Hopefully with some careful optimizations I can keep the improvement in loss while dropping the size of the network.

For now I will continue to collect data and hopefully end up with a model that gives me accurate predictions within 6 seconds of the actual pull time.